2013 - 2014

Notes from the Open Path

Notes from the Open Path - 2013

Dark Lament at the End of the Year

D E C E M B E R 2 0 1 4

So much given, so few who know.

So much beauty, so little love.

-Wendell Berry

What can we say to one another to heal this wound of our regret, of having lived so many moments oblivious to their gift? We’ve had things to do, of course, and now we have more, the twitter of facebook pages leaving us breathless, but can we say we are here the way the rain is here or the way the deer looks up from the grass?

Our cities press against the ground, the traffic halts and moves, and we try to make a living inbetween somehow. We say have no time to ask what matters. Soon that will be true.

We shall go inside now to console ourselves, to make some poor soup of our ambitions, and watch the television. It will tell us what to buy. It will assure us we’re okay watching like this, and that what’s being sold is what we’ve been waiting for.

Who hears anymore the light of the dawn? Who hears anymore the silence beneath our thoughts? Who sees the wind or touches the dark? We have no time, we must go.

Out on the sea, the invincible sea, our debris collects in floating islands stretching out to the horizon and we don’t really care. Are we worthy of this place?

We want our children to have a better life than ours, but their lives are already tainted by our restlessness and the mistakes that came before us. We hope for them but we don’t know what we hope for.

Under the Paris bridge a farmer family from Morocco stretches a cloth to protect themselves. Their baby is not comforted by the thunder of tires above.

Surely, we say, it is not as bad as all that. Surely our pleasantness will redeem us. Surely one day we will clean all this up and beauty will return to us and the sparkles of light on the river will be enough to give us peace.

Here at the end of the year the dark comes early. We pull the curtains and wait in our homes for something good to happen, even though it already is.

We mustn’t fall asleep with these bleak thoughts. Let us say instead our most tender prayers, the first prayers of our heart. In the name of all that is most dear to us, let us re-dedicate our lives to the beauty we forgot. In the name of all that has been hurt, let us vow to love what we love and give that to each other.

Are We Good?

N O V E M B E R 2 0 1 4

I recently attended a talk given by a Buddhist teacher, Mipham Rinpoche, in which he asked this question: “Are we good?” He said this is the central question of our time and the most important global issue. “The notion of human goodness and dignity is doubted,” he said. And then he asked, “Have we given up on ourselves?”

Doubts about our worthiness — individually and collectively — have a powerful influence on our actions. Beliefs such as “I am unworthy, I am less, my life is pointless,” or “humans are selfish, ignorant, and lost,” or "my group is good, but your group is less than human" have led to profound suffering over the course of human history.

Given the welter of violence, suffering, judgments and phobias streaming at us from media, it’s not surprising we doubt human goodness. And as for our own worth, many of us seem unable to resist doubting, comparing, and undermining ourselves.

Basic goodness, basic selfishness, basic nothing — which is it? Where can we look for an answer? This question of human goodness brings to mind Einstein’s observation that, in his view, the most important question we can ask is: Is the universe benign?

Einstein didn’t offer a direct answer to this question, but he did go on to describe three alternative scenarios:

If we decide the universe is an unfriendly place then we’ll use our technology and resources to wall out the unfriendliness, and we’ll create ever-more powerful weapons to destroy everything we think is unfriendly — which will certainly increase our sense of isolation, and may well result in our destroying ourselves.

If we decide the universe is neither friendly nor unfriendly, then we’ll end up feeling we’re victims of random chance and that our lives have no purpose or meaning.

However, if we decide the universe is benign, then we’ll use our skills and resources to better understand and align ourselves with that universe.

Einstein’s three alternatives may give us a clue to answering Mipham Rinpoche’s question, Are we good? or at least how we might begin looking for an answer. Einstein doesn’t appeal to an ultimate source of truth where certainty can be found. Instead he points to the consequences of each alternative response, and we suddenly understand that how we answer is key.

Personally, if I were asked these questions I would answer without hesitation, Yes, we are good, and Yes, the universe is benign. But if I were to justify my answers with some kind of reasonable thoughts, they could easily be rebutted by equally reasonable thoughts. The literatures of religion and philosophy — and the evidence of history — are full of these contrary positions and arguments.

My sense is that answering the question of basic human goodness and dignity is not a matter of uncovering an ultimate truth written in the stars somewhere, or in our DNA. The “answer” is revealed instead in a more immanent way, through a responsiveness arising from the clear, open presence we are, prior to our thoughts and beliefs. The “immanence of response” I’m speaking of isn’t based on a reasonable argument or a religious conviction. It arises simply and spontaneously when we experience our interconnection with all being.

Of course, to access the “clear, open presence we are” is a subtle matter, though at the same time it couldn’t be more obvious. Accessing the clear, open presence we are is the work of continual awakening we dedicate ourselves to, no matter what spiritual path we follow. “Deconstructive inquiry,” “unlearning,” “purification,” “unknowing,” are some of the ways this work of releasing the hold of thoughts and beliefs is described, a work that ends up revealing what is already and always so.

I remember toward the end of his talk, Mipham Rinpoche paused — he had been speaking about the importance of community and taking action together to “uplift” — and, placing his hand vertically in front of his heart, said, “If the basis is no mistake…”

That gesture and those few words touched the clear, open presence we are, the basic goodness that is no mistake. Then he added, “There is power here. We’re all sitting on a very powerful egg!”

Alone with the Alone

O C T O B E R 2 0 1 4

As I write this my wife and I are waiting near a remote canyon in the Great Basin Desert of southeastern Utah. We're waiting for twelve people we've guided out here to return from their three days of solitude and fasting. This is day two.

Each of these people has gone out alone to sit and sleep beneath one of the gnarled juniper trees, or against the base of a red rock cliff. There they hold their fast, pray, consider their life’s purpose and direction, and listen to the silence.

Imagine what it’s like to be out there. There are no distractions and nothing to do. Your eyes follow a solitary hawk turning in a thermal and then it disappears beyond a ridge. You feel the soft movement of air on your face. You wait. Sand runs through your fingers. You watch your thinking mind thinking, and it becomes uninteresting. You feel old like the cliffs, and the story of your entire life becomes present to you, its great loves and little failures, its hopes, its first dreams.

Sometimes rabbit, coyote, owl or lizard comes to you, and you ask her or him questions. You might ask how to see clearly the next steps in your life, and how you can go forward without self-doubt and in full presence. If you're lucky, they show you.

Or sometimes you might cry, remembering some wound of your life. If you decide you want to be finished with it, you might pick up a stone and whisper into it this thing, this wound, until the stone signifies the entire sad affair. Then with great dedication you dig a hole with your hands and bury it, or pitch it into the abyss of the canyon. You make little rituals like this and their significance becomes powerful for you.

Sometime you might imagine this day is the very end of your life, the last one of all your days. Then, as evening comes, you make a circle of stones and step inside it. This is your sacred circle, the place where you will bring closure to your life. You pray, saying whatever you need to out loud to state your intention and make the moment sincere. Then you close your eyes and wait. You wait to see who comes to say goodbye to you. Maybe your children come, or your spouse. Maybe your grandmother comes, even though she’s been dead for many years. Maybe someone comes who has caused you pain, or to whom you have caused pain. You sit with each person, one by one, listening to what they have to say and responding in a way that makes things good between you. In this way you clean up your life.

When night falls, it makes you humble. You see the universe above you. There are no city lights, and with the moon absent as it is at this time, the blackness is complete. Thousands upon thousands of stars are scattered across the heavens. It is utterly silent. As you lay on the earth looking up, you feel as if you're falling outward into endlessness. You can hear your own breathing and the beating of your heart.

You might choose to hold a vigil on one of your nights of solitude, staying awake all night until sunrise. It’s a hard thing to do, to stay awake that long. You prepare yourself by washing your body, and then enter your sacred circle. There you sit in silence, or talk out loud, or sing all the chants and songs and lullabies you can remember. You ask for guidance. You give thanks for your life and for all the people who have cared for you and loved you and taught you. You pray for the healing of the world, for the end of wars, for understanding and compassion among all people, and for the well being of the entire community of life on earth. You do it again, and again. The stars slowly wheel in their great arc.

When the dawn comes it comes with the slowest grace, a pale lightening in the east, then lavender-coral-rose-gold and the faintest blue-white of the approaching sun. Finally the sun pierces the horizon’s edge with a diamond light that is both comforting and unbearable, like a companion who loves you without speaking.

When the sun warms up the rocks you might go to a place where the Entrada stone spreads out, an ancient sedimentary layer that is smooth and curved like skin. You might take off your clothes to be as naked as it is, and lay with your belly against it. Things are simpler, and the stone teaches you about that. You remember your origins.

Often you are hungry, but even if you were offered food you would turn it down, not wanting to abandon the clarity fasting gives your body. “There’s a hidden sweetness in the stomach’s emptiness,” Rumi says. “We are lutes, no more, no less. If the soundbox is stuffed full of anything, no music. If the brain and the belly are burning clean with fasting, every moment a new song comes out of the fire.”

When the final dawn comes on the fourth morning you pack your few things, scatter any ceremonial stones or altars you have made, brush out your footprints as best you can, and return to basecamp and your life among people. You are glad to be back, glad to eat, glad to look forward to a hot shower, but the time spent out there alone with the alone will never leave you. In fact, it will keep working inside you, patiently returning you to your primal perspective and revealing the strength that is naturally yours. It is, to quote Rumi again, “Free medicine for everybody!” The strength and gratitude you feel become a source you can draw upon to give away to others — free medicine. And that’s the whole point. “You go out in order to come back,” our late teacher, Steven Foster, said, “to bring a gift for your people.”

So here we sit, waiting for our brothers and sisters to come back. We pray for their safety and that they will be able to receive what is revealed to them. They are doing a hard thing and need whatever help our prayers might bring. They are doing it for all of us.

The World of Peace

S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 4

Seventy years ago this week, with Allied armies advancing across northern Europe, Tokyo in a firestorm, and the ovens of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen burning furiously, my mother gave birth to a baby boy. My birth at that tortured moment in history motivated my parents to send out a card to their friends announcing "the arrival of a new citizen for the world of peace."

It was several decades before I saw that card, but somehow its invocation foretold a pattern my life would take — idealistic, a little romantic, and repeatedly drawn by the call to be for such a world.

As a child my world was peaceful — I was a happy little guy, curious and eager, with little to complain about. But by the time I reached puberty I’d found the world was anything but peaceful — developers bulldozed the woods I played in, the atomic bomb lurked over us, soldiers killed each other in faraway wars. What kind of world was this?

As I grew older I immersed myself in poetry and protest. Poetry hinted to me of an understanding and beauty far beyond the bland suburban society around me. I joined civil rights and anti-war protests, became a conscientious objector and refused to pay my taxes. I looked for peace in the ideal of young love. I tried living in the remote wilderness, seeking peace far from the mess my country was making. Then through careful guided use of psychedelics (I was lucky) I experienced the selfless presence of being — the ultimate ground of peace — from which all emerges and to which all returns. But these experiences were fleeting and I came to realize, like many of my contemporaries, that I needed spiritual guidance of a more stable nature. I spent many years studying with a sufi teacher, and then with other teachers. During all this I challenged my understanding of the meaning of peace by bearing witness in war zones and in places where peace was threatened by meanness and ignorance, or where beauty was being destroyed by misguided ideas of development and progress.

It’s been a profound and sometimes heart-breaking journey. On this occasion of my becoming a septuagenarian, I want to ask myself — out loud: what, after all these years, have I learned about peace? What could I say is essential to being a citizen for the world of peace?

I could say I’ve learned that peace requires empathy, compassion, and respect for another’s presence and worth. I could say peace appears through every humble act of kindness. I could use more and more beautiful words, like love and creativity, intelligence and curiosity, tolerance and fairness — all these are the necessary precursors of peace. After all, peace is not a static end-state in which everyone gets along — it’s dynamic, spontaneous, self-correcting, and alive. It can spring up anywhere!

But there’s something else I’ve come to feel is essential for peace to flourish, something that’s not often mentioned. Wonder.

The capacity for wonder in human beings seems to me like a rain that makes it possible for all these seeds of peace I’ve mentioned to take root and grow. Where, after all, does empathy and compassion begin? It begins in our wonder at the great mutuality of life, in our wonder at its preciousness. And what is love if not wonder? We say, “You, my love, are so wonderful!” We say, “Life is wonderful!”

When wonder touches us for a moment we’re made speechless. We’re innocent. Fresh. Intimate. Without the capacity for wonder, would creativity have any passion? Would intelligence have any reach? Would there be any joy in kindness?

Wonder was there in the moment you noticed that cloud billowing in the sky, or when you glimpsed the beauty of snowflakes swirling past a streetlight on a winter night, or when you sensed the way your body feels when you’re walking — how it knows how to make all the lilting adjustments of balance and imbalance. Wonderful! What is it that thrills us with a kiss or a caress? What can we call the feeling we have when we smell the angelic fragrance of a baby’s head? Or hold our hand on a pregnant woman’s belly? What can we call the feeling we have at the moment of true contact with another being?

When we lose touch with wonder we become isolated, disappointed with life; we look for satisfaction in power or righteousness or material gain at the expense of others. A society or religion or family or corporation that loses touch with wonder loses touch with what makes everything worthwhile. And when that happens, the possibility for peace is lost. The stern people who made the horrors of the world I was born into, the fascists, imperialists and militarists, and the people who continue making war on life and beauty in our own time, were and are blind to all that is wonderful.

I don’t believe peace is something abstract. It’s not even an ideal. It’s a gift we bring to life every moment we let ourselves wonder. How wonderful wonder is!

Bittersweet

A U G U S T 2 0 1 4

One morning, God knows why, you are swept clean of yourself.

Wonder of wonders! Clear-headed and clear-hearted, you look around.

Things appear as they always have, and yet… you feel a kind of awe everywhere, a silent wondrous clarity spilling invisibly out of the moment.

You sense it’s not an amazement private to you — it’s everywhere! It’s the awe at the start of things, the awe of the fact that anything shows up at all! What can you say about it, this pure radiant generosity? It gives the light in the trees outside your window, and in your eyes, and in the seeing of your eyes. Wonder is its nature — wonder is not just your response to it — your wonder is its wonder!

You feel your heart bursting with gladness. Now you know what the poet Yehuda Amichai meant when he wrote:

Behind all this some great happiness is hiding.

For you — for this moment — the great happiness has come out of hiding. You can’t describe it because it’s what you’re made out of. The great happiness is just how the moment pours forth, awesome and ordinary and not-even-here. You see the phenomena of the world appearing like the play and display of this great happiness — an infinite cornucopia giving forth supernovas and galaxies and a universe filled with light all the way down to the delicate primrose in your garden.

But immediately you sense something else, something coming from within the great happiness — it’s like a cry, a cry so poignant it has no sound. You know this soundless sound. You’ve known it for a long time. You can hardly bear it.

It’s the silent cry of the world. Not just the cry of tragedy, though it’s that too. It’s old. It comes with the world. It comes with being the world. It’s the cry of things mattering, of grief and pain. Bombs drop and splinter through children. An airplane explodes. An antelope succumbs to the lion’s teeth and the herd runs on without her. An old abbey is torn down to make room for a tourist hotel. A white-haired man sits in the park missing his wife, dead these five years. It’s the silent cry of things passing, things that matter.

Now you know what the Chan master John Hurrell Crook meant when he wrote:

Perhaps, ultimately, there is only a great sadness…

The great sadness pierces your heart while the great happiness frees it. Jesus wept, though he knew the truth. Contemplating the world, enlightened Buddha shed that single tear. You know there’s no point in turning your heart to just one or the other — the great sadness and the great happiness come together. They are not to be resolved — they don’t ask for that.

You know what they ask. They ask simply that you accept them, that you accept being pierced and freed by them in the same way you accept your sacred mortal body.

The Beautiful Revolution

J U L Y 2 0 1 4

Many in my generation — those of us who came of age in the 1960’s and 70’s — were swept up by the spirit of revolutions, both outer and inner. Our revolutions were rarely violent, but they were fiery, profound, and have had far-reaching effects on society. The Beat Generation before us threw down the challenge and we took it. We rebelled against the conformism and security-mindedness of the post-war world we grew up in. We hoisted our knapsacks on our shoulders and left home. “Subvert the dominant paradigm!” we cried, fighting that paradigm over its heartless policies on civil rights, women’s rights, the Vietnam War, nuclear weapons, sexual freedom, species extinctions and environmental destruction. We explored the outer reaches of consciousness with psychedelics, sat at the feet of teachers from the East, and learned how to meditate. We went back to the land. We learned how to grow food and chop firewood.

And then we had kids and got jobs. Some say that’s when we copped out, that’s when the dominant paradigm ultimately subverted us.

But that has not been my experience. I believe the revolutionary spirit of those years is still alive and well, though it looks very different than it did then. It has matured, and continues to mature. I see it thriving both in how we conduct our “outer” revolutions — working for social justice, peace, environmental sanity, etc., — as well as in our “inner” revolutions, where we now seek a direct relationship with the divine, a direct experience of spiritual illumination, rather than being content with second-hand accounts.

The idea of a “revolution,” whether outer or inner, can be stirring, even romantic — Aux armes, citoyens! Formez vos bataillons! — but it has a shadow side. Revolutions typically get their energy from polarization, from being against something. In the sixties when my confederates called the police “pigs” it may have roused their courage, but it didn’t change anything for the better; it just made the police mad. We needed schooling in the aikido of non-violence. We didn’t realize that our “against-ness” was working to keep us in the trance of conflict rather than liberating the situation. We didn’t realize that polarization leads to more polarization, that push always leads to push-back.

I received my first lesson in this in my early twenties while hitchhiking to Spain, staying overnight at a youth hostel in Heidelberg. After staying out late I was walking back to my hostel through the dark streets when, a few steps in front of me, a door opened and a man staggered out onto the sidewalk. He was unstable on his feet and obviously drunk.

I stepped around him and kept walking. After about twenty paces I heard him shouting in German. I looked over my shoulder. He was facing me, his arm raised in a fist, obviously angry at me. There was no one else on the street. I turned away and kept walking, but his shouts became louder.

I couldn’t help it — I felt anger roar up in me. What the hell? What right did he have to curse me? I stopped and turned to face him. My heart was pounding and I thought, I can take this guy, he’s older but drunk as hell. I had never fought anyone in my life, not like this, but my anger at his unjustified anger had taken over. I started walking toward him in as menacing a way as I could. He straightened up and started walking slowly toward me. He was still muttering. He was a mean-looking guy about twice my age. It was like High Noon, Gary Cooper facing the bad guy.

Suddenly – I have no idea why – the strangest thing happened to me. I felt myself being lifted up out of my body some distance above myself. I could look down and see the whole scene: the guy walking slowly toward me, me walking toward him, the deserted street. And then I saw the ludicrousness of the situation. Here were two strangers, completely unknown to each other, about to fight. What nonsense! I saw in a flash that this was how wars begin: men take offense, for whatever reason, at other men, and those men take offense back. Then, just as abruptly, I was back in my body, walking toward this guy.

I stopped. He stopped. Then I smiled and started walking toward him at a normal pace. He backed up and put up his fists, thinking I was coming in for the attack. I extended my right hand, gesturing that I wanted to shake his hand. He looked puzzled, glancing up and down from my smiling face to my outstretched hand.

Then his shoulders dropped and a cautious smile came on his face. He reached out his hand too. We shook hands, and then he pulled me to him, embracing me in a big hug, his beery breath against my ear. He was talking a stream of slurred German, which was incomprehensible to me; I managed to say I was an American. He laughed and shouted, “Amereecan! Amereecan!” We hugged again, laughing, not knowing what else to do, both happy to feel the tension drain out of us. Then we backed away grinning, and walked in opposite directions, both of us repeatedly turning around to wave and shout, “Auf Weidersehn! Auf Weidersehn! Goodbye! Goodbye! Good luck!” Our laughter echoed down the street.

Those few moments when I experienced myself looking down at that High Noon scene literally changed my life. It began an inner revolution in my way of seeing and responding to the world. It was a unique kind of revolution, not a revolution against anything, but a letting go of the knee-jerk logic of polarization and the conflict that emerges from it.

Polarization arises because of the dualism inherent in our experience of reality. We presume there is a “self” (or “subject”) in here, and a vast sea of “others” (“objects”) out there. Geopolitically, this gap between self and other shows up as nationalism, patriotism, and fundamentalism; culturally it shows up as racism, sexism, and classism. What is more, as soon as we define the other as “other,” our own identity gets a thicker shell. A few years ago when I was traveling in Iran I heard a remark of Ayatollah Khomenei’s — he said: “If Iran and America ever become friends that will be the end of the Islamic Revolution in Iran.” In other words, as long as we can struggle against what is oppressive to us, our identity will be assured.

This is old thinking, and though it still dominates global culture, I believe its hold on our minds is weakening. In part, my optimism about the maturing of our revolutionary spirit is based on how prevalent “seeing things from more than one point of view” has become in the past few decades. Systems thinking, Theory U, complexity theory, deep ecology, nonviolent communication, cross-cultural communication, interfaith dialogue, family therapies — these and many other systems approaches to human problems are flourishing now in ways unimaginable fifty years ago. We are beginning to see how much the presumed gap between self and other, us and them, human and nature, has pervaded our societies and constricted our ability to get along with each other and support the community of life on earth. We are beginning to see that “self” and “other” exist together. Subject and object co-arise. There is no gap. My safety and fulfillment includes yours. The health of the planet is inseparable from our own health. We are one interdependent, interconnected happening. And the whole thing is alive!

If you feel you already know these things, that’s a sign that the inner/outer revolution I’m pointing to is taking root. We can take heart in the first indications of its presence:

• climate change, resource depletion, the loss of health of oceans and soil, etc., — all of these impending disasters are forcing us to recognize the interdependence of human society with the life of the planet as a whole;

• the Internet and social media have brought the viciousness of war, greed, and other forms of dominance into our homes — we can no longer avoid seeing the failure of these old ways of human relations;

• an increasing number of statements of principles, international treaties, and global declarations (such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) demonstrate the gradual deepening of empathy and ethics in human society;

• instant communication and uncontrolled access to information is democratizing both education and decision-making in ways we are only just beginning to recognize;

• the rapidly-growing global conversation that is now taking place on sustainability, local food production, beauty in the built environment, and a turning toward the pleasures of art and contact with nature.

As for signs of the revolution in our spiritual lives, these too are beginning to appear amidst the decay of old forms of dogma and religious control over our journeys of spiritual discovery. Here are a few of the ways I see it beginning to show up:

• the enormous advances of science in the past century have revolutionized our view of reality, evolution, the origin of life, and the wonder of the cosmos; this “New Story” is evolving our sense of human worth and our reverence for all life;

• the old idea of God as a separate and judgmental entity is evolving into the direct intuition of the all-pervasive presence of sacred unity;

• the fixation on achieving a spiritual reward in the future is evolving into seeking realization of inner peace and wisdom, now;

• our tendency to talk about religious stories and mystical insights is evolving into our welcoming direct experience of the numinous basis of reality;

• chauvinistic identification with one religious tradition is evolving into appreciation of the many ways divine reality is experienced and expressed;

• the isolation of spiritual groups is evolving into a respectful community that enjoys sharing their different styles and devotions.

These are profound changes, both in our outer relations with each other and planetary life, and in our inner experience of being. While I am not naïve about the enormity of the forces rampant in the world that are aligned against these views, I believe those forces are diseased and will not survive in the long run. The “oppositional revolutions” that have been waged against these forces in the past are evolving now into dynamics of change quite unlike anything the world has seen before.

I like to think of this as “the beautiful revolution,” apparent in both the outer and inner realms we are part of. Why is it a beautiful revolution?

• It’s beautiful because it embraces wholeness rather than polarization.

• It’s beautiful because it nurtures communities of conversation and deep listening to address our problems, not division into belligerent, opposing camps.

• It’s beautiful because it recognizes the fundamental “togetherness” of all being.

• It’s beautiful because it derives its energy not from opposition and righteousness but from openness and mutuality, not from objectifying the world around us but from coming into its presence.

I don’t doubt that this beautiful revolution will take many generations to be integrated into human culture as a whole. It’s not going to save us from ourselves any time soon. It may take a hundred years, maybe a thousand — or it could happen tomorrow. However long it takes, I am confident it will happen. I’m confident because the beautiful revolution is grounded in the way things actually are and the way reality actually works.

I know this may sound idealistic considering the magnitude of the problems facing humanity, and all the ignorant forces of selfishness and greed we witness in the world. Indeed, it may be unavoidable that humanity will have to endure major cataclysms in the near future. But this makes it even more essential that we protect the flame of the beautiful revolution from being extinguished. We might think of the beautiful revolution as a great “Yes” that is arising amidst the chaos of “No’s” around us. As the poet Wallace Stevens reminds us:

After the final no there comes a yes,

and on that yes the future world depends.

The Friend

J U N E 2 0 1 4

One of the names Sufis have for God is “the Friend.” This name points to the mystery that beneath all the confusion and pain we may experience as human beings, our lives are pervaded by a most sacred friendship and love. We are safe. Our own being is inseparable from the home ground of all being which is love. Of course it is not always easy for us to recognize how safe and loved we are. This is why the name “the Friend” is used, to help us relax and stop struggling. The name is meant to reassure us. When we feel the intent of this word “Friend” in our hearts, we open ourselves to how the Friend — what is signified by that word — is all-pervasive. We sense that this friendship is the force that blinks our eyes when we blink, that it’s the very texture of our breath, that it’s what hears this thought. The 11th century Persian Sufi Abdullah Ansari put it this way:

All of my eye is filled with the form of the Friend.

Happy am I with the eye so long as the Friend is within it.

Separating the eye from the Friend is not good —

either He’s in the place of the eye, or the eye itself is He.

Of course there is a danger here, to use such a human word as “Friend” to name the all-pervading presence that lights each moment. Like the word “God,” the Friend can also seem to stand outside of us, because it sounds like a distinct personage. Sufi literature is full of attempts to deconstruct this kind of objectification. For example, Ansari again:

The two worlds [of duality] were lost in friendship, and friendship was lost in the Friend. Now I dare not say that I am, nor can I say that He is.

Deconstruction like this not only makes transparent the illusion of otherness of the Friend, it invites something else to happen. A notion like the Friend can seem to be distinctly outside of us as long as we feel there is a distinct inside of us. But when we welcome the possibility that the Friend pervades all things, including our subjectivity, then the Friend is not simply experienced as a divine force external to us, it is experienced as our very self and moment. We become the Friend.

This means a natural friendliness arises as the nature of our own presence. We no longer have to contrive or protect ourselves. We become naturally warm-hearted and non-judgmental toward others and ourselves. We sense the presence of an unfathomable generosity, the same generosity that gives all, that makes this moment appear as it does. This generosity fills our hearts quite naturally. It is a living force that you can’t keep to yourself — it must be conveyed to others. Not only to people, but to streams, mountains, clouds, birds, even to light itself.

Our responsibility — as the Friend — is simply to love all that is. We might think this is a lot to ask, since we have our own problems to deal with, but it doesn't work that way. The deeper our appreciation for all life, the more we realize it is a treasure to be given away. This is where our life becomes playful — in the giving of our appreciation, love, forgiveness, and wonder. We delight in giving it to everything we contact, especially to the next generation, since this gift — the gift of the Friend — is the most precious of all.

Nondual Sufism

M A Y 2 0 1 4

A few years ago I was asked how a “sufi nondualism” expresses itself — that is, what in my view makes an expression of nonduality particularly “sufi.” To adequately answer that question would take a book — or ten of them — since expressions of nondual realization are woven throughout the vast literature of classical Sufism (Sufism with a capital "S"). My response, below, gestures instead toward a simpler, living sufism (sufism with a lower case "s") — a style of responsiveness to life that arises in the present moment and that is available to us whether we consider ourselves sufi or not.

As I understand it, “nonduality” and “nondual awareness” are names that refer to direct recognition of the clear light of timeless awareness that is the matrix of all apparent existence. This clear light is beyond being; it cannot be known as an object of knowledge or named accurately, though it is ever present. Direct recognition of the clear light does not belong exclusively to any tradition or spiritual view. It is our common inheritance.

When we speak of a nondual Buddhism, or nondual Christianity, nondual Vedanta, or nondual sufism, we are referring to particular styles of revelation and expression of this common inheritance.

We in the West typically think of the sufi “style” as heart-centered — sufism as the way of the heart. But this is only part of the story. Yes, sufism is often marked by poetic expressions of warmth, friendliness, and intimacy, but sufism can equally be experienced as penetrating, relentless, and dissident. So any descriptions of a sufi “style,” like this one, are provisional. For myself, I like to think of it as a style of nondual expression that is spontaneous rather than predetermined, subversive rather than safe. It doesn't stay within a particular pattern. Indeed, the expressions of nondual sufism range from silent contemplation of Divine Absence to ecstatic celebration of its Presence.

I think sufic nondualism in this sense might best be appreciated as a fluency of aliveness that resists crystallizing into a system of thought or belief — but then again it does not hesitate to enjoy thought and belief for the delight or communion they may reveal.

As a living style of awakening, nondual sufism is open, free-wheeling, inclusive in view and practice, non-definitive, experiential, non-sectarian, warm-hearted, non-attached — embracing the full range of human experience while settling nowhere, capable of a mystic openness and freedom from attachment that is equally open to spontaneous delight and sensual extravagance. Expressions of nondual sufism are thankful for beauty in all its forms. They recognize happiness and grief and all emotions in between as free offerings of the Unnameable into Itself.

This style of nondual sufism often shows up simultaneously as a way of negation and a way of affirmation – negating conclusion-making while affirming the indefinable. It's a kind of love-mysticism. It loves the edginess and poignancy of human life while seeing through its apparency to the stillness and love within.

Present without agenda, kind without morality, nondual sufism reaches across the seeming divisions between people and societies with the confidence of the light that is common to us all. Unfinished and unpredictable, its transmission is guided by silence and by an intimate wisdom that arises from the unity of embodiment and emptiness.

For the Sake of Others

A P R I L 2 0 1 4

The story goes that in certain Native American tribes when a person became psychologically unstable, she or he was placed in the middle of a circle of tribal members — men and women, children, old people — and required to spin around and around until she collapsed to the ground. The tribal member toward whom her body faced now became her special charge. She was obligated to care for that person, see to their needs, and be their companion and friend. The understanding was that caring for someone else is what ignites personal healing.

When we ache from the pain of loss or rejection, the pain of depression or loneliness, the pain of feeling unloved, or from bodily pain and impending death, the ache can feel agonizingly private to us. We feel alone in our pain: it encloses us in an isolation that feels terribly unfair. How is it possible then to offer care for others?

When Robert Kennedy lay dying from an assassin’s bullet, his blood spreading across a kitchen floor, he opened his eyes and asked, “Is everyone all right?” I like to believe that question eased his homecoming. At least it taught me this counter-intuitive calculus: when you are in need, give.

“Giving” in this way requires a shift in our hearts. In moving from self-concern to “other-concern,” we enter a deeper belonging.

The Native American ritual is charged by the healing power of belonging, not altruism, for altruistic behavior benefits another at one's own expense. The circle of tribal members embraces the wounded person, who returns that embrace. Both are healed.

So to say “when you are in need, give,” is not an injunction to be virtuous or to sacrifice your need in favor of another’s. It is to step from the loneliness of separation into the seamlessness of Being where nothing and no one has ever been separate from anything else. Our absolute belonging is not an idea, nor do we need to make it happen nor make ourselves worthy of it. It’s already and always so.

“Stepping into the seamlessness of Being” doesn’t require us to travel any distance — it may be more accurate to say it steps into us when we allow it to. A generous heart is first of all a receptive heart.

If I feel the need to be seen and loved for what I am, and I sit in that need waiting for someone to respond with what I need, I might sit for a long time and be disappointed. But if I stop waiting and simply give, as best I can, what I’ve been waiting for, my world turns inside out. The connection I longed for is revealed — maybe not in self-centered satisfaction or in the way I expected it, but in a more fundamental belonging that I am now able to receive.

The way this happens is a kind of magic that is always available to us. The distressed woman falls to the ground and when she looks up she sees in front of her an old toothless grandmother. She gets to her feet and approaches the old woman. She takes her hand. What is that warmth that passes between their hands?

The First Moment

M A R C H 2 0 1 4

The clock ticks. The sun rises. Today takes the place of yesterday. This breath gives itself up to this one. My pen point slides on the paper, your eye moves across the words, each moment giving up, letting go.

Letting go is the gift of emptiness, and the genesis of you and me at this moment. How intimate it is! Always beginning by letting go. “The place of release is where it all begins,” a scripture tells us. We appear by vanishing. This is not done once, but always. It is the most common miracle — the entire cosmos refreshing itself every instant.

“Nirvana,” Nagarjuna wrote, “is the letting go of what arises and passes.” This means nirvana — what we might call “refreshing ease” — is present in the way each moment offers itself by letting go. This offering is called the first moment.

The first moment is prior to our thoughts about it. Our ideas can’t touch it. It is the empty clearing that is so close we can’t see it. We can’t see it, we can’t think it, and yet the invisible gift of the first moment is this most intimate heart we share with the universe.

Even though we can’t see the first moment, our life practice must be to never lose sight of it. That is, the letting go that is emptiness must become familiar and present in the same way that space or gravity is familiar and present to us. We must let letting go wash us of our fixed ideas. Luckily the whole universe is working this way, so we have help.

But our life practice isn’t only about opening ourselves to the flow of letting go. Simultaneously we are created. There is no gap between emptiness — letting go — and our appearing as we do. The universe spontaneously appears in its wholeness, including you and me, in this instant. This spontaneity is one way to sense our interdependence with all events everywhere. Everything appears simultaneously now, born of the first moment.

To the extent we experience ourselves to be the intersection of emptiness and appearance, our life practice is working. While it takes utter resolve on our part to recognize this, the practice itself is effortless since it’s how everything is happening already. Our resolve is not a strain, or something we make happen. It is pure faith, radiant in every atom of our being. All we have to do is let go and open.

Opening in the first moment we can be completely devoted to our life and we can take care of it tenderly and wisely. Opening and gliding in the first moment there is no sense we are a separate existence, a self trying to have its way in the midst of everything else. Our responsiveness to what occurs is sensitive and easy-going. Here we are not at fault, nor are we worthy of praise. Here we are calm, though everything is changing and letting go. Our body moves gracefully. Our thoughts and gestures are generous. In the first moment we have nothing to lose. Our happiness is without cause.

Digging In

F E B R U A R Y 2 0 1 4

In the sixties the poet Gary Snyder advised, “Find your place on the planet and dig in.” I took his advice seriously, digging out roots to clear gardens, digging holes to build fences, digging trenches for foundations, drainage pipes, and septic systems. The view from the handle of my shovel helped me love each place I made home, and the sound of my neighbors’ shovels working next to me did the same.

By learning to dig in—literally and figuratively—I became a neighbor: living under the same weather, walking on the same ground, sharing the patience needed to live in a place and care for it. But the borders of my home-place have not remained secure. The fences I’ve built get climbed over, the gates left open, and the world finds its way in. Faces stare out from the newspaper page and TV news—the taut faces of hungry people half a world away. Children on street corners in desert towns watching soldiers pass by. Faces and voices and stories unknown to me. Who are these people? Whose neighbors are they? What is important to them? Why is their land under seige?

These questions have made me put down my shovel more than once and go on the road, more like a pilgrim or wayfarer than a tourist. Some outer, credible purpose usually motivates my journey, but inside I’m looking for that moment when the ground shifts—when humor or sadness or a shared recognition makes the distance between “my” world and “the” world beyond my borders vanish, at least for a moment.

Once, in Bethlehem, I was invited for a mid-day meal at the home of a Palestinian family. Their flat, perched on top of a three-story hillside building, had been in the direct line of fire between Israeli forces and Palestinian fighters holed up in another building on the hilltop. Israeli bullets lodged in their walls.

My host told me their old refrigerator had been punctured by machine gun bullets, causing it to defrost and the meat in the freezer to thaw, leaking a red stain across the floor. Their three year-old son had pointed at it and said, “Look Daddy, they killed the fridge!”

We all laughed. Then we were silent, our eyes turned to the stain. I glimpsed the world with a three-year-old's eyes. Yes, I was just a stranger passing through, but I became their neighbor too in that moment. Digging in to a place as they had, and traveling through as a wayfarer as I was doing, are about the same desire: to bring the world close. But they do this in markedly different ways.

The indigenous villagers of the Pageiyaw tribe of northern Thailand—whom I visited and worked with for a decade—mark the span of their lives by literally digging in to the soil. They bury their dead among the trees they call “the ancestor forest,” and in an adjacent area known as “the umbilical cord forest” they place the placenta of newborns precariously on a tree branch. After some days, when the placenta falls to the ground and dissolves into the soil, it means the infant will survive and will henceforth belong to that land all its life.

In contrast, the wayfarer doesn’t bring the world close by anchoring to a home-place, but by listening to its stories as he or she moves through, and then telling those stories to other people in other places. Maybe it can help the ones who have dug in avoid becoming suspicious of people not of their place — a kind of peace-making — at least that’s my belief and my hope. In any case, the wayfarer isn’t a tourist: she doesn’t stand back but enters in, asks caring questions, listens, and shares. She weaves the world together, bringing diverse people close with her caring attention.

For a number of years I worked on a project called the Abraham Path—a meandering dirt path that follows the proverbial footsteps of Abraham from the ruins of Harran in southern Turkey, where he was “sent forth,” through Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, to the town of Hebron where Abraham and Sara have their resting place. Hospitality and kindness to strangers are hallmarks of walking this sacred ground. The path is now well established in many parts of the Middle East, and for a while it looked like the Syrian government would allow pilgrims to pass through. But then the peace-making power of such a path worried the Syrian government. They realized this kind of cross-border path would allow a free flow of wayfarers across the land; it would bring people walking like pilgrims do, vulnerable and open. They would meet each other face to face, and tell each other their stories. This seemed too risky to the Syrian power-holders. After nine trips to Syria, I was blacklisted and not allowed to enter again.

Over the past twenty-five years I’ve filled my passports with hundreds of stamps marking border crossings. My travels through the checkpoints between Israel and the West Bank are not marked in those pages, but those crossings are some of the most vivid in my memory. As a wayfaring American, I could pass where people dug in on one side of the line could not easily cross to the other. Though they lived only a few miles apart, they never met.

The bleeding refrigerator in Bethlehem had belonged to Palestinians. On that same trip I visited an isolated hilltop enclave of orthodox Jewish settlers established in the middle of the West Bank. I wanted to speak with the old rabbi who founded the settlement, a well-known teacher of mystical Jewish texts. By the time I arrived a cold wind blew intermittent rain over the dark hills. The place was dug in like a fortress, isolated from the land around it. My Palestinian driver left me at the gate, saying he did not feel he should be there. He told me to call a taxi when I was ready to leave.

The several young families who had come for teachings from the rabbi that evening were trying to quiet their fussing children, who were clearly ready for bed. The rabbi—with long white hair and beard, bushy black eyebrows arching over kind eyes—gave them blessings. It was a scene of intimate tenderness. One by one the young families left. The weary rabbi seemed genuinely disturbed that my Palestinian driver had not felt comfortable visiting, even though he was his neighbor. And then he told me of his deeper sadness. The Israeli Prime Minister had just slated his settlement for evacuation. Twenty-seven years of digging in would simply end. I thought of Gary Snyder and how all boundaries bend to time.

The rabbi walked me back to the guardhouse to meet my taxi. He asked the young soldier if I could wait in his little tin guardhouse out of the cold. The wind moaned through the cracks in the squalid hut. Hebrew graffiti were scrawled on the walls, and one in English read: “What am I doing here? What am I doing here?” The Israeli soldier stood there silently, with his machine gun slung over his shoulder, looking down the hill for anything that might be approaching. I felt the neighbors there, so close yet un-meeting. I felt the little orthodox children drifting off to sleep nearby, and the child of my Palestinian friend dreaming of the murdered refrigerator. The graffiti echoed: “What am I doing here? Why am I not in my own peaceful home far from here?"

But I knew the answer. I was simply supposed to be there, feeling exactly this bittersweet recognition that I repeat now: the ground we dig into and walk upon is sacred. It is sacred because it makes us neighbors to each other, whether we like it or not. Tell this story.

This piece was written for the forthcoming anthology, "Loving Dirt," edited by Barbara K. Richardson — a book that charts the ways we humans love and depend upon the soil beneath our feet.

Slogans for Myself

J A N U A R Y 2 0 1 4

At the beginning of this new year I’d like to share with you a few reminders — “slogans” — that often help me open to the ineffable reality of this moment and its gift of ease. Sometimes I say one of these slogans to myself, sometimes I simply feel their meaning without any words. They help me especially when I have become tangled in self-identity and experience myself as something separate. Some of these reminders are straight quotes from people like Ibn Arabi, Longchenpa, Inayat Khan, Tsongkhapa, Kerouac; others have sifted through my life who knows how? I hope you may find one or two of them helpful in your own daily practice.

Remember.

The clear light hasn’t gone anywhere.

Where this moment starts — free medicine!

It wasn’t in a greedy mood that you saw the light that belongs to everybody.

As clear as space, it can’t be seen. No use trying.

It can’t be known. It is the knowing.

You can’t get it in the future because you already have it.

You can’t have it because there’s no one to have it and nothing to have.

It isn’t an it. It’s what lights you up.

Know all things as pristine purity like the sky.

All things are made of the same thing which is nothing.

From the inside out and the outside in, no edge.

You are not you.

Your body isn’t yours. It belongs to the cosmos.

There is nothing but God. God is all-in-all.

Open me Lord and let me flow.

Open into openness.

Don’t believe your opinions.

Enlightenment comes when you don’t care.

Volition obscures awareness. Will precludes attainment.

Turn up the volume on the quiet.

Take me away from myself and be my being. Then shall You see everything through my eyes.

Emptiness is the track on which the centered person moves.

Easy does it.

Each moment is self-liberated.

Serenity is the letting go of what arises and passes.

Everything that happens, let it happen.

Everything is all right, and even when it isn’t, it is.

Love one another.

Being here together is enough.

The Breath of the Median Void

D E C E M B E R 2 0 1 3

“Music is what happens between the notes.”

— Debussy

I sit here at dawn listening to the city awaken. My neighbor’s footsteps on his front stairs. A car door closing. The first traffic on the street, tires on pavement. A bus pulls up outside, the squeak of its brakes as it stops, a little hiss, and the rattle of its engine as it waits. The electric hum of the refrigerator in the kitchen.

Above my head a few dozen miles the air thins to nothing. It is quiet. The silence up there goes on into space forever. Beneath me, beneath this building, in the rock down there, it is quiet. My life is played between two silences. One silence, hidden from me.

My body breathes. I don’t do anything. This breath is not the breath that preceded it and it is not the one that follows. It is already gone. I don’t know where it has gone, or where it came from. Hidden.

I wonder what I am. I look, for the millionth time. Nothing there. I can’t find what’s thinking this thought. My interiority seems continuous, but there’s nothing in there. Whatever it is, it’s hidden from me.

I seem to be that which arises between something and nothing, between sound and silence, between what is revealed right now and what is hidden right now. My living moment is here — in this space — where the Hidden and the Revealed encounter each other.

Is it really a space? Here where the Hidden and the Revealed encounter each other, where my breath appears and vanishes, where I am neither something nor nothing, is there any dimension? I look. I don’t find any dimension. And yet it’s vast, beyond distance.

This is the space Taoists call the Breath of the Median Void. It is fundamental, they say, to the Great Breath (qi) that animates the living universe. The Breath of the Median Void arises where the Yang Breath — the power of the active (the Revealed) — encounters the Yin Breath — the power of the receptive (the Hidden). Here. Where I am, without being anything.

Everything that makes my life worth living occurs here, in the Breath of the Median Void. Everything. When I pick up my little grandson and he lays his head on my shoulder. That gesture meets the silence of the eternal — right there on my shoulder. He and I, nothing in ourselves, touch.

My body grows old. How beautiful this life has been — the pleasures, the awakenings, even the losses, the grief. All of it summed up in this moment now and swept into the Hidden. Utterly vanished. What is left is this breath, this Void, this love.

Seeing the One World with Two Eyes

N O V E M B E R 2 0 1 3

Even though we humans live in nonduality, we experience the world with the two eyes of duality. This is because we have the ability to conceptualize. Even to say the word “nonduality” is to conceive dualistically. When we say “nonduality” our minds are already at work, setting up nonduality here and duality over there.

It’s helpful to remember that perceiving dualistically is not a fault — it’s the way we’ve been made. If I say the word “I” it means I have conceived of myself as a subject, and this is natural enough, isn’t it? “I” wake up in the morning, “I” brush my teeth, “I” love you, and so on. It is a convenient way to think, even if it is not exactly how things work. Phenomena arise not as subjects and objects, but as a whole, all at once.

Nevertheless it’s not easy for us to see the wholeness of things because we see — for good reasons — with the two eyes of duality. Making distinctions between “this” and “that” makes it possible to navigate in the world. But if we cannot also see through the convenience of dualistic thinking to the nondual nature of being that is ever-present and all-pervading, we bind ourselves to a life of suffering.

A Zen master once remarked, “We must learn to realize nonduality through duality.” Is this possible? Can the two eyes of duality see the one world of nonduality?

That is to say, can we realize the truth without abandoning this world? Or, in Buddhist terms, can we realize the nature of emptiness without betraying the nature of form? Can we realize, as the Sufis say, that nothing matters and that everything does? Can we grieve the loss of a loved one even while we know nothing is lost?

In nondual teachings we often find phrases like: “everything is perfect as it is,” or “nothing ever happened,” or “this is all a magical display.” Statements like these, while true, seem to deny what we also know to be true: that everything is not perfect as it is, that something is happening, and that, magical display or not, this world is beautifully, heart-breakingly real.

I once held the hand of a young woman as she died. She was wide awake when the moment came. I could say that nothing actually happened at that moment — it was like the space inside a jar “meeting” the space outside when the jar breaks — nothing really happened — and yet…

There is no way to think about this. Only the heart can encompass it, and the heart doesn’t think. To see the one world with two eyes (Rumi’s phrase), we have to allow the heart to see through those eyes. The seeing heart is like a musical instrument that lets the song be played but doesn’t cling to any melody. The beauty of our lives, the love, the losses, the injustice and cruelty we witness — the only way we can bear all this without turning from it, or hardening ourselves, or becoming overwhelmed, is to bear it in the open tenderness of our heart.

And what is that? What is the heart? Here we have to stop conceptualizing. The heart we call our own is not ours. We might say it’s God’s heart, or the heart of the All-Good, or the One. It’s the heart inside of things. Through it flows all the experiences of beauty and all the despair that has ever been and ever will be. The heart I am trying to point to is not a private thing. It’s vast, boundless. It bears all. It sees the one world because it is the one world. It doesn’t limit or exclude anything. As Jack Kerouac reminds us,

Not in thoughts of your mind

but in the believing sweetness of your heart,

you snap the link and open the golden door

and disappear into the bright room, the everlasting

ecstasy, eternal Now.

True Movies

O C T O B E R 2 0 1 3

Guest Contributor: Puran Lucas Perez

My father’s mother’s brother’s wife once turned over a card in a Tarot reader’s tent and at that moment the gypsy, Etheria, gasped.

Taking this as a sure sign of looming misfortune the wife prepared an herbal protective which — upon drinking down — caused an embolism in her obliging husband’s brain. Killing him.

Her brother’s death meant that my grandmother became the sole heir of substantial properties, titles, and noblesse oblige in the province of Cadiz. My father, her eldest, stood next in that line.

Knowing this would forbid him from marrying the comely house maid he had impregnated he fled to South America, leaving the maid to the Sisters of Mercy, who took my mother in.

Midwifing me into the light, Sister Ignatia, had a divine revelation: I was an angel sent, and she was meant for mothering, not rosaries. So off she stole me one night into the wide world.

Years later, in London, my train was delayed one Friday while a suicide was cleared from the tracks. Rushing across Regent Street I knocked into a lovely young woman, who pirouetted artfully out of harm’s way.

I married this ballerina who, on an opera tour through the Balkans, had an affair with a wild-haired conductor. (Thus our second daughter’s implacable curls.) She confessed this, fading out of life, holding hands in a cancer ward.

Our curly-haired daughter wed a bright young broker who whisked her off to Wisconsin and a moneyed life among the glitterati. As if trying to rectify her bloodline, she became a pillar of convention, a crusader of normalcy.

But her youngest son, quit Harvard Law and in the throes of sexual awakening, ran madly off with a young composer; only to find it was the music maker’s sister he really loved. He wound up running a B&B with her in Boulder, Colorado.

It’s tempting to say the inception point of all these movies was Madam Etheria’s gasp on a rainy Spanish afternoon. But we might just as well say it was the bad sausage she had for lunch that caused her to stifle her burps that day.

The Everyday Practice

S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 3

As a young man searching for truth I found a Sufi order and asked for instruction. My teacher gave me a series of practices, among which was a simple breathing prayer: “Open me Lord, and let me flow.” I was told to silently repeat on my in-breath: Open me Lord, and on my out-breath: and let me flow.

As a very earnest young student I took this practice to heart, repeating it whenever I remembered — sitting on my cushion, walking down a street, opening a door, preparing a meal, raising a spoonful of soup to my mouth. Open me Lord, and let me flow.

Unlike many in my generation, I didn’t have a problem with the word “Lord.” I wasn’t raised in a theistic tradition so the word didn’t resonate for me with authoritarian patriarchy — it just signified everything I didn’t understand about reality, all the awesome forces at work in the universe. Since I was a typical self-conscious young man tangled up in my thoughts and emotions, I had no confidence that I could open myself, but “Lord” — this incomprehensible power behind all things — to this I could appeal and submit. Open me Lord. Let me flow.

I repeated the prayer so often that the words became transparent to me, silent, leaving just a visceral motion of opening when I breathed with this intention — like a swing swinging in the open air. It became “my familiar,” and still is.

A few days ago, visiting a friend’s house, I saw these words from Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche written in a framed calligraphy:

The everyday practice is simply to develop a complete acceptance and openness to all situations and emotions, and to all people, experiencing everything totally without mental reservations and blockages, so that one never withdraws or centralizes into oneself.

There it was. The entire teaching of my little breathing prayer was inscribed in Khyentse Rinpoche's sentence. His words don’t tell you how to respond “to all situations and emotions,” they don’t give you any moral guidance. They simply indicate the naked openness by which life can be lived most authentically.

The final phrase is particularly penetrating: ...so that one never withdraws or centralizes into oneself. How familiar is this movement of withdrawing and centralizing into oneself! Don’t we do it a thousand times each day? Things get hectic, we’re late to work, someone cuts us off, someone criticizes us, our family takes us for granted, we feel inadequate, or lonely, or without a meaningful future. Centralized into our self we join the world’s neurotic drama. But at least we think we know what’s happening; we have a point of view.

It takes profound trust to open from our solid point of view, from our withdrawal. Perhaps this is the utility of the word “Lord:” surrendering to universal forces you don’t understand, that are beyond your point of view. Open me Lord.

But there is something strange here. What is the “me” that is opened and that flows? When the me opens, is it any longer a me? When the me flows, what flows?

Here is the heart of this everyday practice. This is where it changes from words and good advice to in-your-face truth. Here we have to stop thinking, and look for ourselves. What “me” opens?

When we look, we don’t find anything! There is simply open, clear perception, immediate and naturally spontaneous.

Shabkar Lama, a nineteenth-century mystic-minstrel of the Tibetan plateau, speaks beautifully to this same question: What “me” opens?

Do not look at the vision but look for the viewer. Looking for the viewer, if you fail to find him, then your vision is at the point of resolution. This vision in which there is nothing at all to see but which is not a blank nothingness, is vivid and unalloyed perception of the here and now…

No viewer, no meditator, no actor, no me! Just this vivid openness, free of a me, free of withdrawal into a myself. This vividness, this freedom, is what flows, all by itself. Breathing now, Open me Lord, and let me flow.

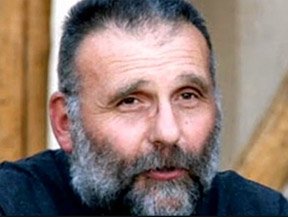

To Jesuit Priest

Father Paolo Dall-Oglio

A U G U S T 2 0 1 3

Dear brother Paolo,

The news this morning told me you “may already have been shot.” I don’t want to believe it. I don’t want to believe it so I am writing you now, pretending you will read this, pretending the world couldn’t be that stupid to push you, of all people, out of itself.

I know you would say the world did the same to Jesus, so why not to you, his servant? Is that why you went back into Syria, to be like him? Is that why you walked down that street in Raqqa last week, looking for the hideout of the al Qaeda militants to plead with them to stop killing the Kurds?

When Stephanie asked you, before you left, not to take unnecessary risks, you told her, “I have been thinking of the words of the disciples to Jesus in the gospels before he died. ‘Must you go to Jerusalem?’ they asked. And the answer is yes — sometimes you must go to Jerusalem. You must go with your physical body in order to be there.”

To be there — there — between the anger and the hurt, between the Salafi and his Armageddon, between the bullet and its target, you stand your innocence. Did it already happen? Did you face him when he raised his gun to your wide chest, did you look at him with those tender eyes of yours, did you say, “Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim,” “In the Name of God, the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate,” did you say, like al-Hallaj,

I see my Lord with the eyes of my heart; I ask Him, Who art Thou? He says, “Thou.”

And the fighter, in the moment of your love, did he lower his gun, his eyes moist with recognition?

Yes! The centurion refuses to pound the nail! Pilate runs up, takes Jesus’ hand, begs forgiveness! The clouds part, they sit at a table, they share bread and wine!

Paolo, I do not call you foolish for going there. You had to. My prayer, like yours, is to the finger on the trigger — that it unclench its fright, that it remember its own innocence, as it was, so recently, on a baby’s hand in a soft-sheeted crib. Have mercy! Be mercy!

I remember sitting with you late at night on the desert cliffs outside your Syrian monastery, the great sweep of the Milky Way above us, talking about God, war, and love. I remember drinking wine with you in Barcelona next to Gaudi’s cathedral, raising our glasses to its happy spires. I remember when we painted a great peace prayer flag and stretched it across the gorge at the monastery. It filled in the wind like a spinnaker, and you, you stood on the rooftop chanting in your booming voice, “Allah ismuhu’ salam!” God’s Name is Peace!

I watched as you raised your arms up, turning in slow circles, heard your immense voice filling the canyon in all directions, “Allah isamahu’ salam! Allah isamahu’ salam!” and one by one we joined you, we humans below, calling out, reaching up, the sun in our eyes, “God’s Name is Peace!”

Brother, whether you lay cold and still now on a slab somewhere, or break bread with the people at a sunlit table, telling stories to lift their hearts, you live. You live in the brave, generous spirit you show us. May we be worthy of it.

Before I Die

J U L Y 2 0 1 3

I sat on a bench in a park with a man who had been given his final diagnosis. That long afternoon he spoke to me from his heart, his words dream-like, drifting in and out of fantasy. When we said goodbye I went home and tried to write down what I remembered he said, but most of it had vanished. These are the few lines I could recall:

I’d like to get it right before I die

live without leaving a trace

put the world in order

tidy up

I’d like to tell all the girls they’re loveable

and all the boys they’re good

so they’d smile all the way down into their bones

at the simple fact of it

I’d like to bow back to those trees

swaying their crowns in the sunlight

I’d like to say something so wonderful

that everyone would stop

for a moment

surprised by the sudden remembrance

that they already know what this is all about

but forgot

light playing on the wave of emptiness

this All-Good, All-Bliss, Home

I’d like to tell my children

there’s no need to worry or be sad

and they’d believe me

except of course for the sadness we can’t bear anyway

of appearing and disappearing like this

so dear

with none of us able to adequately hold

or honor the precious moment of love we love

I’d like to tell God how thankful I am

and have that telling mark the end of time

Before I die I’d like to walk into

everyone’s most intimate space and tell them

everyone

every man woman child I have ever known

that they are my favorite, the special one, my beloved

I’d like to take this great carpet of the world

in my two hands and give it a shake

send a wave through it that would shake free

the ugliness we’ve done to it

I don’t know what will happen when I die

and I’m glad for that

what I do know is it will be more awesomely loving

and beautiful than I could ever imagine sitting here

That’s my faith I guess

Here I remember he became quiet, gazing into the sunlit foliage of the park in front of us. It felt like he wanted to say something more but didn’t know how. A young mother walked by wheeling a pram, followed by a little boy trailing a stick in the gravel path. After they disappeared he spoke again.

No it’s not my faith

I’m sure of it

I’m as sure of it as I am of this moment

how it is

so kind

after all our worrying and hating

still so kind

The Fable of Coyote and the Void

J U N E 2 0 1 3

The Void sat on a rock, staring blankly into space.

Coyote approached him. “You look blue,” she said. “What’s up?”

“I don’t know,” the Void said. “Something’s missing, that’s all. It’s like I want to write a love letter but I don’t know my lover’s address. I feel like I could burst into a million million pieces. It hurts.”

Coyote sat down next to him. “That’s a big problem all right,” Coyote said. They sat there quietly for a long time.

“I have an idea!” Coyote said. “You need to make something, something different from you! You need an up and a down, darkness and light, that kind of thing.”

“What good would that do?” the Void asked.

“Well,” Coyote suggested, “it might give you an address for your letter.”

The Void considered this. He shook his head. “That’s pointless,” he said. “Anyway, the thing about the love letter was poetry. I didn’t mean it literally.”

“Okay,” Coyote said. “Just a thought.”

They sat quietly again. Then Coyote sat up straight. “I’ve got it!” she said.

“What?” asked the Void.

“Look, you have to make it more interesting. Start with things like darkness and light, up and down and so on, just to make sure you’ve got an over here and an over there, a subject and an object, and then…”

“Wait a minute,” the Void interrupted. “How could I do that? You know I can’t be divided.”

“Just pretend!” said Coyote. “Make believe you can! Look, pretend there’s a sky. Color it blue or something, put clouds in it, then pretend there’s an Earth underneath, halfway up. Plant things in the Earth and…”

“Wait!” the Void blurted. “You’re getting ahead of me!”

“Just listen,” Coyote said, “I’m on a roll. Make the plants all different shapes and colors, and make wind blow through the sky to move the clouds and let the growing things sway about. Then you could send your love letter — or whatever it is — to all of them. What do you think?”

“Mmm, quite the picture,” the Void said. “Still, I don’t see the point.”

But Coyote’s enthusiasm wasn’t dampened. She jumped up and turned to the Void, exclaiming, “There’s more! Pretend there’s little creatures everywhere that could move around on their own — some could fly, some could swim, some crawl, some walk. I’m sure they’d all love to read your letter!”

The Void tried to imagine what Coyote was describing. “Well, maybe,” he said, “but I’m not sure they’d be interested in my letter. Anyway, there’s another problem.”

“What’s that?”

“Too much work. Those creatures and growing things would wear out. I don’t want to have to keep making new ones.”

“Right, right,” said Coyote. “That is a problem.”

“Although, I suppose we could let them do it,” the Void offered. “I mean, put them to work making more of themselves.”

“You’d need to make it fun,” Coyote said. “Otherwise they wouldn’t bother.”

“True,” said the Void. “That means they’d have to want to. That means desire. Lots of problems with that.”

“You’re right,” said Coyote, stumped.

They decided to leave it for the day, to let the idea simmer.

The next morning the Void was walking by himself contemplating Coyote’s scheme. It was good, he could see that, but it was still missing something, something important.

He met Coyote. “I’ve been thinking,” he said.

“So have I,” Coyote replied. “Something’s missing, isn’t it?”

“Yep. Your idea is nice enough, what with blue sky and clouds, and creatures walking around underneath and making more of themselves, even allowing for the problem of desire, but in the end, there’s still the question…”

“I know what you’re going to say,” Coyote interrupted. “What’s the point?”

“Exactly,” said the Void.

“But what’s the point of your love letter?” Coyote asked. “That’s what started all this, after all.”

“Shhh,” said the Void. “You just gave me an idea.”

Coyote sat patiently, eyeing the Void.

Suddenly the Void shouted, “I’ve got it!” His eyes were bright. “Oh yes!”

“What?”

“We’ll make the Beautiful!” the Void cried. “The most wonderful, happy, glorious, radiant, majestic, sacred and tender Beautiful that ever could be! All the creatures will love it, and their love for the Beautiful will become an answer to my love letter!”

Before Coyote could say another word, the Void spun around, his arms outstretched, spinning so fast a whirlwind rose up, encompassing both of them.

The whirlwind grew to be a Beauty as vast as all vastness, becoming more beautiful than the Void and Coyote ever could have imagined.

“Now that was a good trick,” Coyote said when she caught her breath. “But now we have another problem.”

“What? What could be a problem?” demanded the Void, proud of himself.

“The creatures and all those growing things,” Coyote explained, “they’ll see the Beautiful and won’t even bother to move, or for that matter bother to make more of themselves. They’ll just stand in awe. No desire.”

“You’re right,” the Void said, instantly deflated. “What to do?”

Coyote winked at him. “I know,” she said.

She leaned over and whispered in his ear. “Hide it,” she said.

“What do you mean,” asked the Void.

“Hide the beautiful! Hide it inside everything! Just let a little Beautiful shine out at a time so all the beings don’t get dumbstruck. Then they’ll want more. They’ll see the Beautiful glinting out of each other and that’ll start them hugging and making more of themselves, and they’ll see it peeking out of the sky and clouds and everywhere, and they’ll love everything and care for it and their love will be their letter back to you!”

“Perfect!” the Void cried out, and that word rang through the vastness. He embraced Coyote and cried out, “Yes! Now all the creatures will desire the Beautiful, loving what is just out of their grasp! The clouds will be making beautiful to mimic the Beautiful inside them they can’t see, the sky will be making beautiful, the growing things will be making beautiful, the creatures of all kinds will be making beautiful, making beautiful as they make themselves! My letter will be received and answered!”